Conservation case study: Ainu hunting quiver

What might appear to be dirt on an object can convey important information about its life prior to acquisition by the Museum. Conservators are always aware that such dirt might help recount the object's story to us. For instance, the encrusted soot on an Ainu hunting quiver has revealed a fascinating account of the people and history that surround the object.

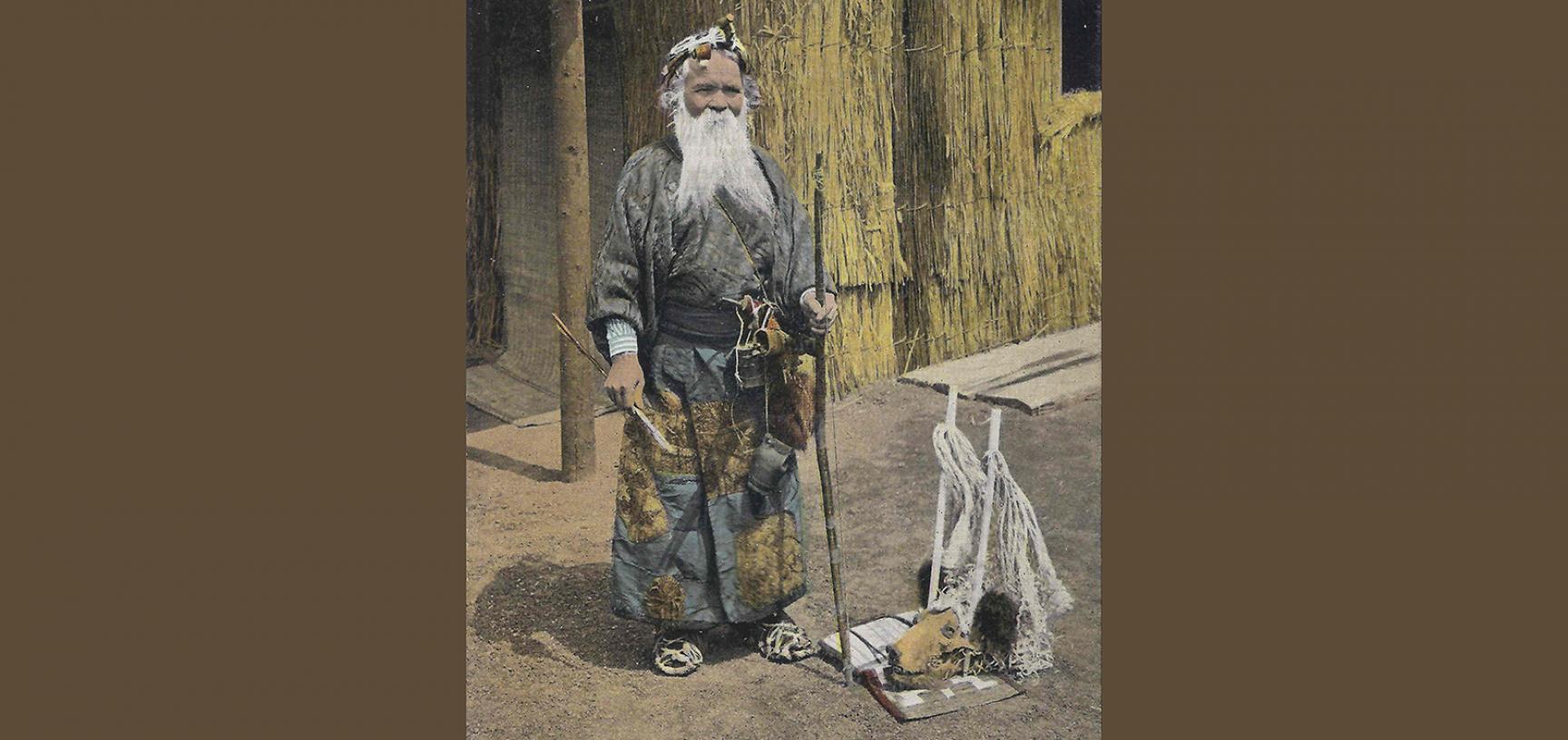

The quiver was purchased for the Pitt Rivers Museum at the 1910 Japan-British Exhibition in London, for which a group of Ainu delegates were brought to live on-site as representative colonial subjects of the Japanese empire. Displays of people in reconstructions of their traditional homes, were popular in international fairs at the turn of the century.

During an assessment in the conservation department, the team noted that the object had numerous signs of wear and repair which suggested its long-term use, such as repairs to the torn bearskin shoulder strap. Most curious of all was a dark-coloured encrustation of soot covering a large part of the object's surface and the two distinct layers of willow shavings wrapped around the quiver: a soot-covered under layer and a fresher upper layer. Such willow shavings are considered to have been inau, a term to describe something used as a channel between spirits and people in Ainu cultural practice.

Subsequent consultation with the Historical Museum of Hokkaido (Hokkaido Kaitaku Kinenkan) in Japan, informed us that similar encrusted soot had been found on other historical hunting quivers. It was considered possible that the accumulated soot could originate from the quiver being stored above a kitchen fire, where traditionally a shelf was located in historical Ainu houses.

A series of hunting bans had been imposed on the Ainu by Japanese authorities from the mid-1800s. With hunting a vital part of the economy, the bans had a serious impact on the Ainu people, who attempted to gain a reversal of the measures. The hunting apparatus may have been stored in the Ainu home for an extended period of time, accumulating soot and cooking fat, waiting for the time when it could be used again.

Conservators endeavour to find ways of analysing materials without the removal of samples from an object. However, sometimes this is not possible. In this case, three small samples, each the size of a pinhead, were taken from discrete areas of the quiver's surface. The samples were analysed in an attempt to identify fat content and kitchen soot. Sadly, the results were inconclusive, partly due to contamination of the object's surface by pollutants since its acquisition.

The hypothesis of the soot bearing witness to the historical experience of the Ainu community remained a strong factor to be taken into consideration when deciding on the conservation treatment for the quiver. Intervention should be kept to a minimum so as to leave any significant historical deposit intact. Fragile elements, such as the severely splintered sillow shavings (inau) and unraveled bark bindings, were stabilised as they were vulnerable when handled. A custom-made storage box with an internal support was also made for the object, to minimise handling when the object is studied.

The condition of the two layers of inau remains in question. It seems possible that the Ainu delegate who owned the quiver may have wrapped a new layer of inau over the old layer in order to renew its efficacy in ensuring their safe sea voyage to Britain. The object may reflect in some part the personal experience of the Ainu delegates at the Japan-British exhibition, whose own voices left little mark in the written records.

A total of 126 hours was spent working on the quiver, with 26 hours on conservation treatment and 100 hours on research.