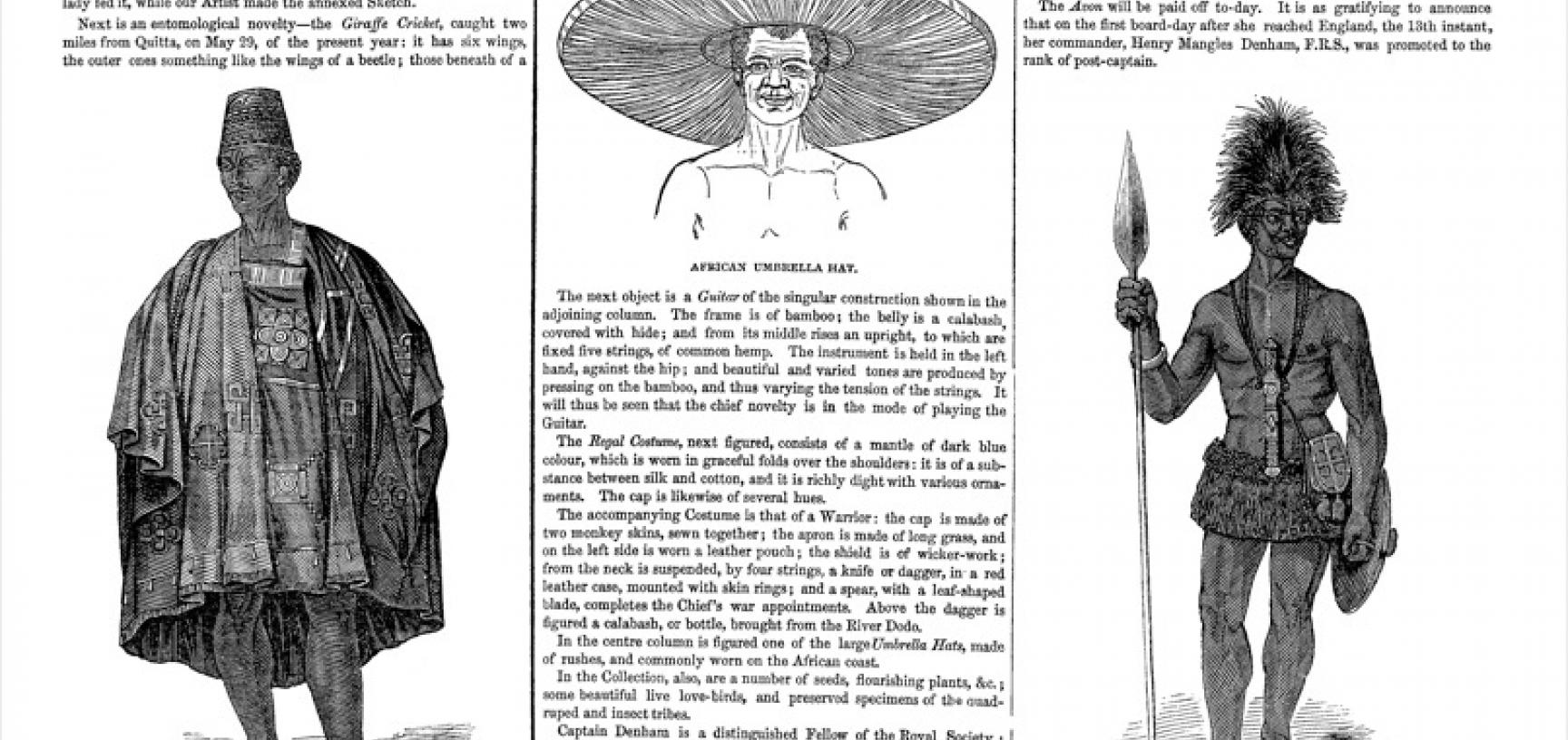

Costume of a King

Documenting a Lost History

In 1974, this gown was found in the Pitt Rivers Museum’s textile store without any documentation or accompanying information. Museum staff identified it as ‘probably West African, possibly Nigerian’.

A few years later, visiting researchers Venice and Alastair Lamb identified the gown as being from eastern Sierra Leone or northern Liberia, and dated it to around 1900. They published a photograph of it in their book Sierra Leone Weaving (Roxford Books, 1984).

In 1998, Museum staff realised that the gown was probably part of the Museum’s founding collection that had been given to the University by Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers in 1884. They matched it with an entry for a cotton garment or tobe in the Museum’s accessions register (1884.90.2): ‘Large dark blue tobe with coloured embroidery. W[est]. Africa’. Pitt-Rivers is now known to have acquired it by March 1874.

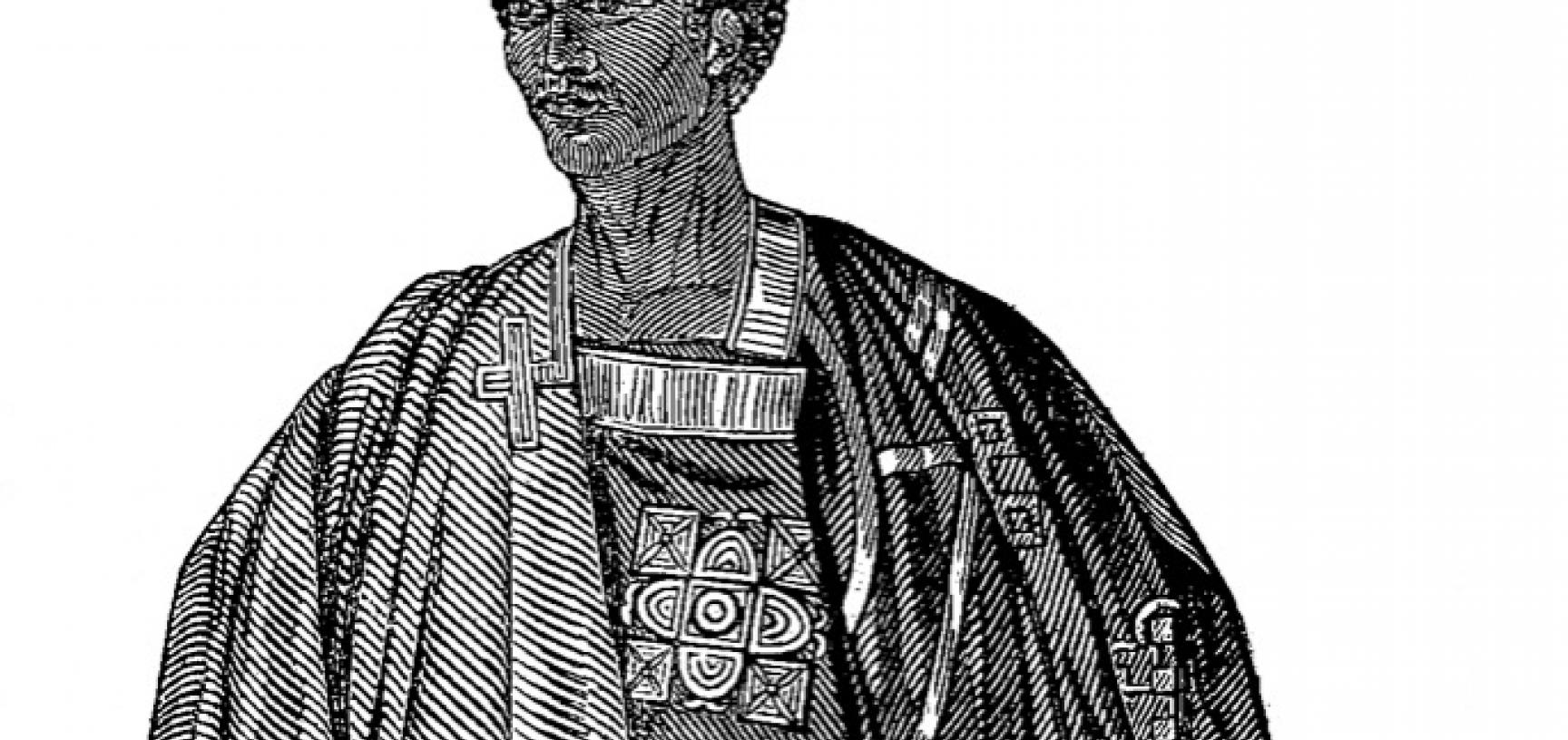

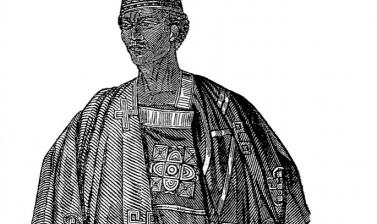

In September 2009, West African specialist William Hart, of the University of Ulster, sent the Museum a photocopy of a page from The Illustrated London News for the week ending Friday 28 November 1846. He suggested that the gown illustrated in the figure captioned ‘Costume of a King’ is the same gown. Careful comparison of the image and a photograph of the gown arranged on a mannequin has shown this to be so.

The article in The Illustrated London News reports on the return to London of Captain Henry Mangles Denham, who had spent a year in command of the steamship HMS Avon surveying the coast of West Africa. Denham had brought back with him ‘a number of curiosities botanical, zoological, and ethnological’.

According to the journalist, ‘the report of them was so promising, that we dispatched one of our Artists to the steamer, lying at Woolwich, to sketch the most attractive of these novelties’. The accuracy of the artist’s sketch of the gown is quite remarkable, a testimony to his skill and professionalism.

Thanks to the detailed descriptions and illustrations in The Illustrated London News, it has now been possible to identify the ‘African Guitar’, pictured on the same page as the ‘Costume of a King’, with a previously unprovenanced instrument in the Museum’s founding collection. Museum staff have also now concluded that a few other items in the founding collection that have long been associated with Denham – including a decorated gourd, a paddle and a spear – were probably collected by him on the same voyage. Work to document these items continues, as does the attempt to identify the current whereabouts of the other ‘curiosities’ collected by Denham and described and pictured in the article.

Costume of a King

This embroidered cotton gown is from Liberia or a neighbouring area of Sierra Leone or Guinea. It was made in or before 1846, when it was brought to London by Captain Denham of the HMS Avon. Such a well-made and beautifully embroidered gown would have been made for a chief. It may have been presented to Denham as a gift or acquired from a trader. Bernhard Gardi (of the Museum der Kulturen in Basel, Switzerland) has traced the whereabouts of 23 such gowns, of which this is now known to be one of the earliest.

The basic structure was made by sewing together locally woven narrow strips of handspun cotton that had been dyed dark blue with indigo. The sides were then partially sewn up, leaving wide armholes, and a large square pocket sewn on to the front. The embroidered designs and the band of imported red material were added last. The cotton was prepared, spun and dyed by women; the weaving, sewing, and embroidery was done by men. Rectangular and straight-sided gowns such as this are known generally as kusaibi.

The style of the embroidered designs is characteristic of the work of Mandinka artists in the area of north-western Liberia and neighbouring Sierra Leone and Guinea. The indigenous meanings of the motifs – and their arrangement – have not been recorded. However, it seems certain that the central motif of five interlocking squares should be understood in relation to the frequent use of five-element motifs throughout Islamic Africa. These were regarded as having protective or ‘amuletic’ properties, against the evil eye for example. Aside from such meanings, the quality of the cloth and the extent and elegance of the embroidery would have demonstrated the wealth and status of the wearer.

The style of embroidery on such gowns has been described in detail by Venice and Alastair Lamb: ‘The front pocket is outlined by a rectilinear design made up from a continuous line or set of lines which starts at the upper right hand corner of the pocket (as seen by the wearer) and then goes down and round to the upper left hand corner where it terminates either just below or just over the left shoulder of the wearer. Each time this line or set of lines turns through a right angle it does so by passing through a set of three rectangles before making the turn, a veritable maze of an arrangement. On the front pocket, enclosed by this design, there is a central motif … usually a square consisting of four circles or circles in squares at the corners surrounding a central circle or circle in a square.’ (Venice and Alastair Lamb, Sierra Leone Weaving (Hertingfordbury: Roxford Books, 1984), p. 137.)

Acknowledgements and Credits

- Exhibition researched and curated by Jeremy Coote

- Case design and installation by Adrian Vizor

- Special thanks to Venice Lamb, Alastair Lamb and William Hart

- Supported by the Leverhulme Trust

![Sir Henry Mangles Denham (1800–1887) in 1849; from a lithographic portrait by Charles Baugniet, printed by M. & N. Hanhart. The original lithograph is signed ‘Baugniet 1849’ and the print is signed ‘Yours tr[uly] H. M. Denham’. (Copyright National Portrai Sir Henry Mangles Denham (1800–1887) in 1849; from a lithographic portrait by Charles Baugniet, printed by M. & N. Hanhart. The original lithograph is signed ‘Baugniet 1849’ and the print is signed ‘Yours tr[uly] H. M. Denham’. (Copyright National Portrai](https://prm.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/listing_slideshow_image_thumbnail/public/prm/images/media/costume_of_a_king_image_4.jpg?itok=XANtBDJ4)