Ma uka to Ma kai

The ahupua‘a, a land division extending from the mountains to the sea, has long been the cornerstone of sustainable land management for Kanaka Maoli (Hawaiian) communities. "Ma uka" (toward the mountains) and "Ma kai" (toward the sea) are not merely directional references; they signify a deep understanding of care and access to natural and cultural resources within these regions.

Through a combination of contemporary and historic mea noʻeau (skillfully created works) this special exhibition explores the past, present, and future of the ahupua‘a system. Hawaiian quilts by the Honolulu-based Poakalani Quilters are curated in narrative that follows the ahupua‘a and the people working with the landscape, from mountain forests to the coastal waters, and as well as introducing the Hawaiian royal history of the palatial grounds of their group meeting place.

Join us on a journey through time through the ahupua‘a in this special exhibition: witness the disruption of indigenous practices over the past 150 years, accompanied by a decline in Hawaiian ecosystems, alongside stories of resilience and restoration. Travelling from Ma uka to Ma kai, discover efforts of contemporary practitioners who embrace 21st-century sustainable stewardship, and how looking back towards traditional practices offers a glimpse into a future of abundance and harmony between communities and their environment.

Here, some highlights from the exhibition are shared, introducing the main themes and some of the items on display.

Journey across the Hawaiian Landscape: Ma uka to Ma kai

Back to the Future with Ahupua’a

A place-based land management system, the ahupua’a is a division land from the mountain to the sea that historically supported self-sufficient communities.

Ancient Hawaiians recognized the pilina (connectedness) between the land and sea, rainfall and vegetation, preserving the integrity of the balanced ecosystem in conjunction with intensive land/water use. The past 150 years has seen a disruption of indigenous practices, like the ahupua’a system, accompanied by a marked decline of Hawaiian ecosystems. Today, about 90 percent of the food and supplies needed to sustain the islands population is imported.

Using the Hawaiian quilting works of the Honolulu-based Poakalani Quilters as the primary visual medium, traverse the ahupua’a with practitioners whose work embraces a 21st century sustainable stewardship and looks back towards a future of abundance.

The Hawaiian Archipelago and the Ahupua’a

The Hawaiian archipelago is an isolated chain of eight major volcanic islands and several atolls located in the mid-Pacific Ocean. The Hawaiian Islands are grouped as part of Polynesia, and believed to be first inhabited by voyagers from the Marquesas islands in 300 CE followed by Tahitians in 1200.

An ahupuaʻa is an ancient land division system used in Hawaii, which usually extends from the highest regions of the uplands (ma uka) to the sea (ma kai). The Hawaiian ahupuaʻa were similar to land units used in other Polynesian islands, but were territorial as well as being social-familial. The term ahupuaʻa, comes from the very demarcation of said territory; referring to an ahu [altar] decorated with the head of a pua‘a [pig] situated at the boundary of the land section.

Although of many shapes, sizes, each ahupua‘a consisted of three distinct areas: mountain, plain, and sea. However, these areas were all connected through the flow of wai (water), especially streams. Streams would begin up in mountain forests, flow into the plains, and then empty out to sea. These streams provided the people living in the ahupua‘a their wealth. The foundation of the system lay on laws of Kānāwai or shared water usage.

A brief history: the Hawaiian Kingdom and the Ahupua’a

In 1795 Kamehameha the Great, united the islands under a single rule for the first time. He redistributed land according to tradition among local ali'i (chiefs). Konohiki (head land steward) oversaw how Kanaka (people) used land within each ahupua'a (land segment). Under this system there was no private land ownership, all were entitled to a share of what was produced from the soil or taken from the sea.

The great land division

The Great Māhele (great land division) of 1848 was an attempt by King Kamehameha Ill to protect land from being appropriated by foreign powers and interests even if sovereignty was lost.

It transformed the lands of Hawaii from a shared value into private property- a system recognised by looming colonial forces.

The land was divided amongst the crown, alifi and konohiki (chiefs and managers) and the government. The intention was to encourage Native Hawaiians to submit formal claims of ownership to the government lands. However, this ultimately failed due to rampant corruption. The result was that areas were snapped up by foreign investors for purposes such as commercial farming and the whole system of the ahupua'a began to break down.

In 1893 the Hawaiian Monarchy was illegally overthrown, and Queen Liliuokalani imprisoned. The Government and Crown Lands were consolidated and confiscated by the United States to be managed as a public trust.

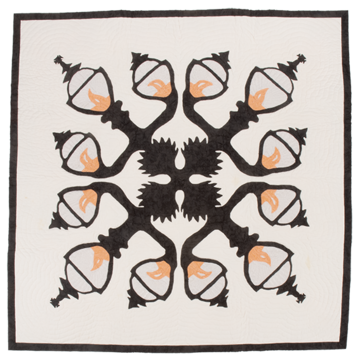

Kukui ʻo Hale Aliʻi. Quilted by Yuko Nishiwaki. Designed by John Serrao.

The quilt that I donated to the museum is the Lights of the Iolani Palace. The Iolani Palace was the first to have indoor Electricity even before the White House. This quilt represents my love for the Palace, the friendship I found there at the quilt classes where I came every Saturday to quilt.

Yuko Nishiwaki

Kukui ʻo Hale Aliʻi translates to Lights of the House of Royalty (Palace), and is referring to the lights outside Iolani Palace in downtown Honolulu. Today Hawaii is known as one of the fifty states of the United States of America. However, until its annexation in 1898, Hawaii was a kingdom ruled by the ali‘i. The Iolani Palace is therefore the only royal palace on U.S. soil. Construction on Iolani Palace began in 1879 and was completed in 1882. The Palace was the official residence of the Hawaiian monarchs, where they held official functions, received dignitaries and luminaries from around the world, and entertained often and lavishly. The Palace is also the site of imprisonment of Queen Liliuokalani, the last ruling Hawaiian monarch during the overthrow by the US government. Since then the Palace has served many functions from being the Capitol to a multicultural epicenter of Hawaii, representing the thriving dignity of the people of Hawaii.

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the palace was where the Poakalani quilters gathered every Saturday for class. The Palace holds much significance to the quilters, but also is a representation of history and sovereignty.

Ma uka

Towards the mountains

Ma uka (mountain) lands have been occupied for over 1000 years. The Hawaiian Islands have a diversity of ecosystems, even within the ma uka areas. Snow-covered alpine tundra, high-elevation bogs, mesic and rain forests. Within the ahupua‘a, the ma uka regions hold significant cultural value.

Wao akua - The realm of the gods

The Hawaiians recognise two broad ecological zones, the wao akua, the realm of the gods, and wao kanaka, or realm of people. The wao akua are the upland areas and are revered by Hawaiians as places of spiritual renewal. Many of the upland flora and fauna have been thought of as physical manifestations of deities and the spiritual realm. Because of these species' proximity to the godly realm, there were often strict protocols around how upland resources were used.

Forest resources

The health of the ahupua‘a is dependent on its water. High elevation tree canopies capture mists and rainwater that replenish the islands' groundwater supplies. Springs then provide drinking and irrigation water for Hawai‘i's communities and agricultural sector. Native trees such as the ‘ōhi‘a lehua, which makes up 80% of Hawaiian rainforests, are particularly effective as living sponges.

From the ma uka also comes resources such as: koa, kauila, and ōlona trees, used to build everything from canoes and hale (houses) to rope. The upland forests also provide shelter and food for native fauna, including the Hawaiian honeycreeper birds, innumerable insects, and many other species.

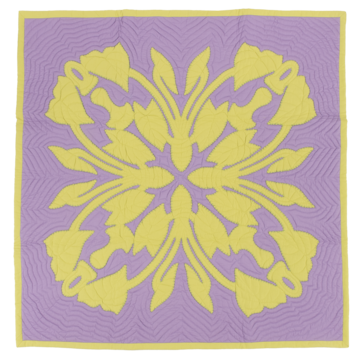

'Ōhi'a Lehua quilt. Quilted by Susie Sugi. Designed by John Serrao. PRM 2022.57.1

‘ Ōhi‘a lehua

Haai no ka ua i ka ululā‘au - the rain follows the forest

The ‘ Ōhi‘a lehua quilt depicts the ‘ōhi‘a lehua tree's beautiful red needle-like flowers. The ‘ōhi‘a tree serves a key role in watershed protection and water conservation by retaining water following storms, preventing erosion and flooding. The wood of the ‘ōhi‘a was traditionally used for tools and weapons. Its nectar-rich flowers provide an important food source for native honeycreeper birds, which provided the feathers on feathercloaks. In recent years the ‘ōhi‘a tree has come under serious threat from a fungus called Rapid ‘Ōhi‘a Lehua Death (ROD) which quickly kills ‘ōhi‘a trees and is threatening the water security of the islands.

Lovers' tears: Translating the ecological into the cultural

In Hawaiian cultural imagination the ‘ōhi‘a lehua is most associated with rain. The saying pōki‘i ka ua, ua i ka lehua (the rain, like a younger brother, remains with the lehua) refers to how rain drops cling to an ‘ōhi‘a forest. The ecological function of the ‘ōhi‘a lehua is even embedded into the tree's creation myth:

‘Ōhi‘a and Lehua were young lovers. The volcano goddess Pele fell in love with the handsome ‘Ōhi‘a, but he turned down her advances. In a fit of jealousy, Pele transformed ‘Ōhi‘a into a tree. Lehua was devastated. Out of pity, other gods turned her into a flower on the ‘ōhi‘a tree, or some say Pele was remorseful, but unable to reverse the curse, turned Lehua into a flower herself. When a lehua flower is picked and separated from the ‘ōhi‘a tree, rain will come representing the separated lovers' tears.

The ‘ōhi‘a is one of the first plants to start growing after a lava flow and is closely associated to Pele. For this reason, the tree is also used to describe people who are strong and resilient.

Kula

Kula are the flat and sloping lands between the uka and kai. The kula is considered to be in the Wao kanaka or realm of man, region where people live and work and daily life of man takes place. Within the wao kanaka Hawaiians engage in farming, food preparation, weaving, and constructing hale. The kula can be called the bread basket of the ahupua‘a, where many food plants are grown. The quilts Kalo, Hua ʻAi, andʻUlu all represent staple crops and fruits in Hawaii. All this foods can be found in the kula region of the ahupua‘a.

A significant feature of the kula is the lo‘i kalo, which are irrigated terraces for growing wet-land taro, a root crop. Kalo is a staple in the Hawaiian diet and is pounded to make poi. The kalo terraces are built near the kahawai, ‘the place having fresh water’ as it was a key to the working of the irrigated terraces.

However, the growth of plantation economy in the 19th and 20th century, severely disrupted the flow of wai leading to drastic changes to the ‘breadbasket’ and food security. In Hawaiian the word for wealth is waiwai, it is the life blood of the ahupua‘a system.

Kalo

Kalo especially dear to Hawaiians as within local understanding kalo is literally the elder brother to humans. Hawaiian moʻolelo tells of Wākea, Father Heaven, who bore a child with the Daughter of Earth. The infant, Hāloa, was born prematurely in the shape of a bulb. Wākea buried the body at one corner of his house. The couple’s second child, also named Hāloa, was born healthy and would become the ancestor of the Hawaiian people. Hāloa was to respect and look after his older brother for all of eternity. The elder Hāloa, the root of life, would always sustain and nourish his young brother and his descendants.

A lo’i kalo is a traditional Hawaiian irrigation system used for growing taro, a staple crop in Hawaiian culture. Lo’i kalo consist of a series of terraces or shallow pits that are dug into the ground and lined with rocks or other materials to retain water. Water is channeled from the water source into the lo’i kalo, where it is used to irrigate the taro plants.

Kalo (Taro). Quilted by Kimi Kumagai. Designed by John Serrao. PRM 2022.57.7

Stolen Waters

An important feature the irrigation system used to grow kalo is ho‘iho‘i ika wai, the return of water back to the stream. Kalo farmers understand that the water coming in to the kula also had to service those in the ma kai region below. The lo‘i kalo also acted as a buffer to filter pollutants and slow down the surface water flow, reduce sediment and protect the fishponds and coral reefs where the water meets to the sea.

Today, thousands of acres of lo‘i kalo have dried out. The water which fed them was diverted to sugar plantations during the 19th and early 20th century. Millions of gallons a day flowed through a new network of tunnels and ditches with no respect for the needs of the ahupua‘a and the Kānaka Maoli - the local people - who lived on them.

The creation of plantation ditched heavily impacted the fertility of the land and threatened native food security. From the mid-20th century, the sugar industry declined, but the Board of Water Supply who took over are focused on supplying water for domestic and urban use. The needs of the ahupua‘a are not taken into consideration.

The parched earth coupled with increasing climate change have left Hawai‘i vulnerable to intense fires. On 8 August 2023, the town of Lahaina, Maui suffered tremendous loss due to fire made more serious by the continued diversion of water. Historically, Lahaina was the favoured lush and cool residence of the Hawaiian royals. Today, much of the island's water is channelled into hotels and golf courses, perpetuating the water theft of the early 20th century.

Who owns the water?

Ka’ala Farm and Restoring the wai‘wai (wealth) of Wai‘anae

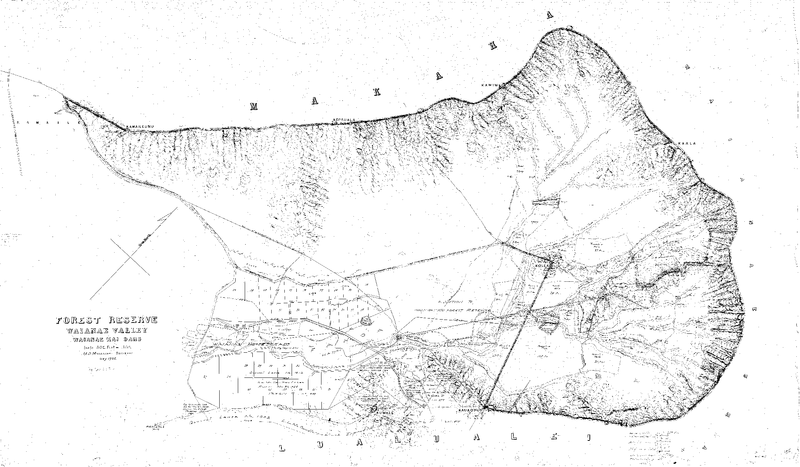

Map of Wai‘anae Valley Forest Reserve. M.D. Monsarrat. 1906. Registered Map 2372.

This 1906 map shows that 250 acres in Wai‘anae Valley were ‘formerly in taro cultivation'. The map also marks the 18 tunnels and ditches created to pipe water from over 20 streams to the Wai’anae Sugar Company’s cane fields. The verdant valley that once supported thousands of Hawaiians was turned into dry fields forcing them to abandon their way of life.

In the 1970s, teacher, Eric Enos, led a group of students on a trip into Wai‘anae Valley and came across the remnants of the kalo terraces and the plantation ditch that syphoned off the water.

Using the 1906 map and lo‘i kalo walls as evidence, Enos successfully petitioned to restore some of the water from the plantation ditch into the stream. With the restoration of water into the valley's ancient kalo terraces, he founded Ka’ala Farm and Cultural Learning Center to combat the growing issues of poverty, food security and loss of local knowledge.

Enos continues to pose the questions to his students:

Who owns the water?

Who owns the sun?

Who owns the wind?

Back road blues:

Mending the spirit and growing the community

Wai‘anae suffers from what Enos refers to as 'the back road blues'. Enos describes the forced disconnection between kānaka and the ‘āina (people and land) as creating a spiritual illness.

Today, the residents of Wai’anae are 68% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander compared to 26% for the rest of the island. They earn 20% less than the state average, with poverty levels hovering near 20%. There is also an exaggerated perception of Wai‘anae as a dangerous place.

At Ka’ala Farm, Enos and his team are working towards mending that connection between people and land:

We’re all just reawakening – plants for food, medicine, fibre, adornment, spiritual uses, shelter – all those things that our traditional plants were, how were they used. This is a great movement for us, to go back to the land and to find the water and to grow again as a community.

Eric Enos

Ma Kai

Hawaiian understanding encompasses the ocean, coral reef and sea life as major component of the islands. The ocean is the great highway between the archipelago and the wider Polynesian culture. In the past, Hawaiians were more intimately aware of life cycles of marine resources, and managed them sustainably, because their existence depended on it. Most settlements were located within the kula-makai region (the area close to the coast).

The ocean is not viewed as separate from the mountains or fields that make up the ahupua’a. Its health and vitality is connected to that of the land. The wai (water) that flows from streams into the sea is not considered a ‘wasted’ resource, but is recognised as essential to the ecology of muliwai (estuaries), which are breeding grounds for many aquatic species.

Nā Iʻa o Ke Kai (Fish of the Ocean) Kala, Heʻe, Pyramid Butterfish, Humuhumunukunukuāpuaʻa Quilted by Rae Correia, Susan Lessa, Cissy Serrao, Midori Andrews. Designed by John Serrao. PRM 2022.57.10

Feeding the Community

The border around each of the four samplers of the Nā I'a o Ke Kai quilt call to mind a unique aspect of the ma kai in Hawai‘i, which are fishponds. Loko i‘a kuapā or walled coastal ponds are unique to Hawai‘i. Most Hawaiian fishponds were built between 1200 and 1600, and were constructed using basalt, a volcanic rock and coral. The size of fishponds ran the gamut from large 560 acres, to small ponds of less than an acre for use of a particular family.

Although Hawaiians did partake in ocean fishing, it could be unpredictable, dependent on many external factors. The purpose of the loko iʻa kuapā, was to cultivate pua (baby fish) to maturity. The success of fishponds was a result of the Hawaiians' deep understanding of the environmental processes specific to the islands.

By allowing both fresh and salt water to enter the pond, the pond maintains a brackish water environment and creates the ideal habitat for limu (algae) to proliferate. By cultivating limu, much like a rancher grows grass, the kiaʻi (guardian) could easily raise herbivorous fish and not have to feed them.

Once 500 fishponds across the islands fed Hawaiian communities. Today there only about 4 working ponds. Famous areas such as Pearl Harbour and Waikiki were once home to upwards of 40 fishponds. Increasingly shifting economic patterns, the overthrow and annexation of the Hawaiian government, time, and natural disasters led to their decline the 20th century. These fishponds offer the opportunity to provide physical and cultural sustenance. An effort is underway to restore the pond structures and reconnect communities to their aquaculture past.

The place where the fishpond breathes

He‘eia Fishpond

In the ahupua‘a of He‘eia, on the island of O'ahu is an impressive 800 year old fishpond. The kuapā (wall) extends away from the shoreline, completely encircling the 88 acre fishpond. The kuapā is estimated at 1.2km long and 5m wide. The pond has seven mākāha (gates), four on the seaward side that regulate the flow of seawater and three along the He‘eia stream to regulate the input of freshwater. Mākāha translates 'to the place where the fishpond breathes'.

Today the loko i‘a (fishpond) is stewarded by the community organisation Paepae o He‘eia. For the last twenty years, Paepae o He‘eia has worked to restore hundreds of metres of pond walls destroyed by devastating flood in 1965, and by the root systems of invasive mangroves introduced in the 1920s.

Revitalisation of the fishpond depends on more than the rebuilding of the structures. The continued diversion of fresh water from the ahupua‘a poses a major problem. Found of Paepae o He‘eia, Hi‘ilei Kawelo describes the wider challenges:

When we started doing the restoration work here, we never thought about 'oh, we wouldn't have ample enough water.' Yes, a lot of water goes to residential areas. A lot of it, I think is wasted on watering things like golf courses. Some of it goes to our military bases. It's not that I'm saying that we shouldn't give water to our neighbours and to our people. We want it to work, we want the system to work. We want to be able to grow fish. But if fresh water is the limiting factor, then we have to have those conversations with folks that are in positions of power

The sewing together of rocks

Paepae o He‘eia's crew work on removing the dense mangrove and restoring the rock walls using Hawaiian dry-stack method or uhau humu pōhaku, which literally means 'the sewing together of rocks'. The team are called Kū Hou Kuapā meaning 'let the wall rise again'.

Keahi Pi‘iohi‘a, head of the Kū Hou Kuapā crew describes the artistry of wall building and the importance of pōhaku (rocks):

The sewing of together of rocks, that's how we explain it, our kupuna (ancestors) were very poetic. And when you do it, you realise the sewing technique that you're capable of, that it's not just a bricklaying type of stack. It's all dry stack, no mortar. And yes, we literally try to sew together the rocks. And quilts are in the same line. This is pōhaku version of a quilt, literally the interlocking and the interjoining of rocks to make something.

Quilting the Ahupua'a

In 2020, curator Marenka Thompson-Odlum began working with the Honolulu-based Poakalani Hawaiian Quilting group as part of a contemporary collecting project at the Pitt Rivers Museum. The aim of the project was to work collaboratively with artists, makers, and practitioners to challenge the narratives often presented in museums about their specific cultures and/or localities. Thompson-Odlum relayed a simple brief to Cissy Serrao, current head of the Poakalani group and daughter of its founders:

'the quilts should reflect the stories and knowledge that the group wanted to share with our audiences.'

Cissy Serrao reflects

The quilts took over two years to complete. One reason of course was Covid, which completely shut down our fabric shops, where we needed to purchase our supplies. Second, we were originally commissioned to create only one large quilt complementing the 'ahu'ula (feathercloak) that is in the Pitt Rivers Museum. However, it seemed that one quilt couldn't really tell the story of Hawaii. So, we decided that we would make five smaller quilts, but when word got out to our quilting classes about the commission, many of our quilters wanted to be part of this amazing project. The Pitt Rivers Museum now has 15 new Hawaiian quilts in their collection. All the quilts together tell an even broader history of Hawaii. It reflects who we are as a people, our culture, and traditions, but the quilts themselves also tell the personal stories of the amazing quilters who created them.

The unintentional narrative that arose from the quilts was that of the ahupua'a, highlighting the intricate connection between Hawaiian cultural practices, knowledge, language and place. The 15 quilts capture various aspects of the nature, culture, history, and ever-changing dynamic of Hawai'i.