Marina Abramović @ Pitt Rivers Museum

The Artist’s Research in the Museum

In the summer of 2021, the pioneering performance artist Marina Abramović undertook a research residency at the Pitt Rivers Museum in preparation for an exhibition at Modern Art Oxford. That residency inspired elements of her Gates and Portals exhibition at Modern Art Oxford and this installation at the Pitt Rivers, which features new video work and drawings by the artist.

For Abramović, the residency was a kind of homecoming, as she had previously developed seminal video works for an exhibition for Modern Art Oxford in partnership with the Pitt Rivers in 1995. Her now famous work, ‘Cleaning the Mirror’, was exhibited at the Pitt Rivers Museum at that time.

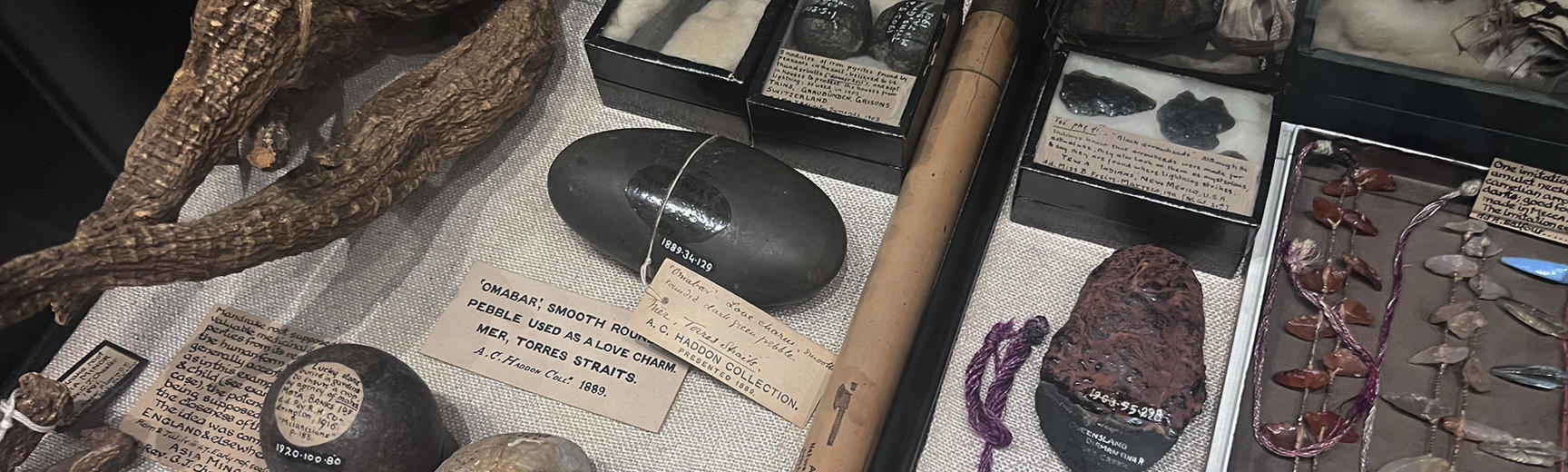

On her return to Oxford in 2021, Abramović spent a month conducting research in the Pitt Rivers, reading, drawing and filming with the objects she had selected from the museum’s global collections. She particularly focused on items associated with magic, rites of passage, sites of transition and transformative states of consciousness. When making her choices from among the tens of thousands of objects on display. Abramović stated that she was drawn to certain things by the powerful energies they emit, since she believes that “like human beings, animals and trees”, they each have their own aura. Walking among the Pitt Rivers’ densely packed displays of material from all over the world, Abramović said that she “did not choose the objects. They chose me”.

Marina Abramović on the Pitt Rivers Museum from Pitt Rivers Museum on Vimeo.

The Case Display

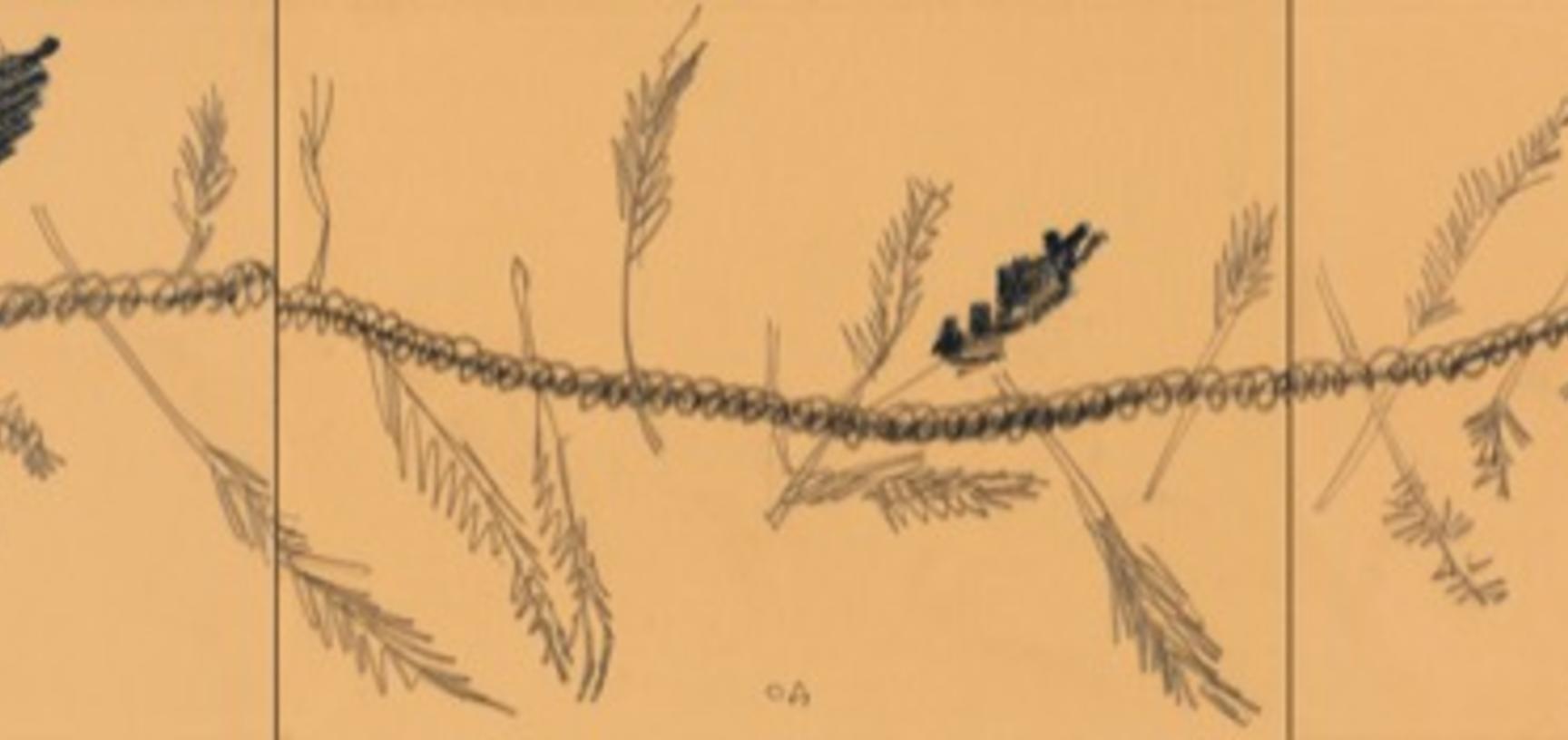

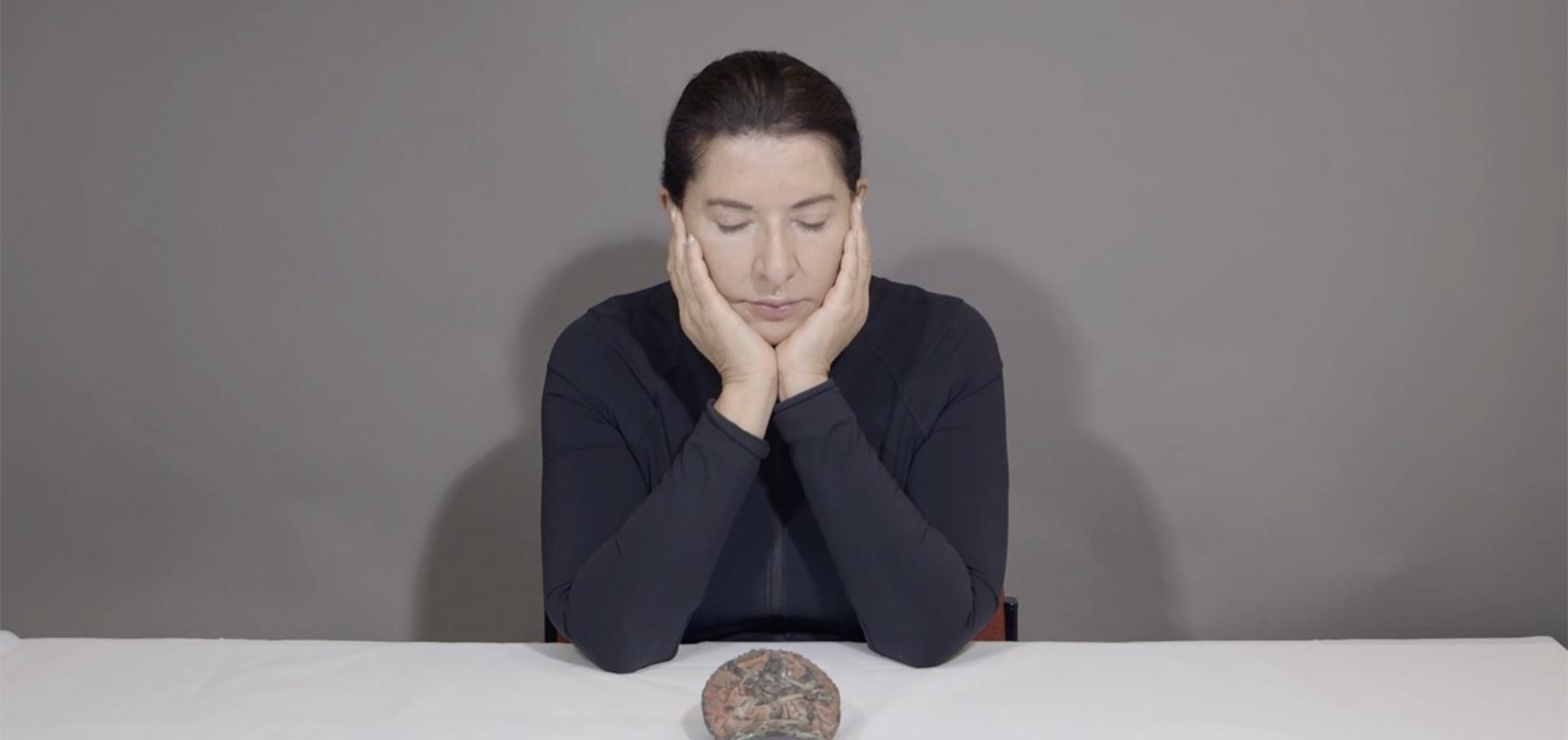

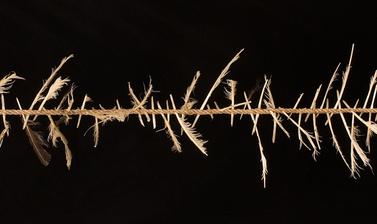

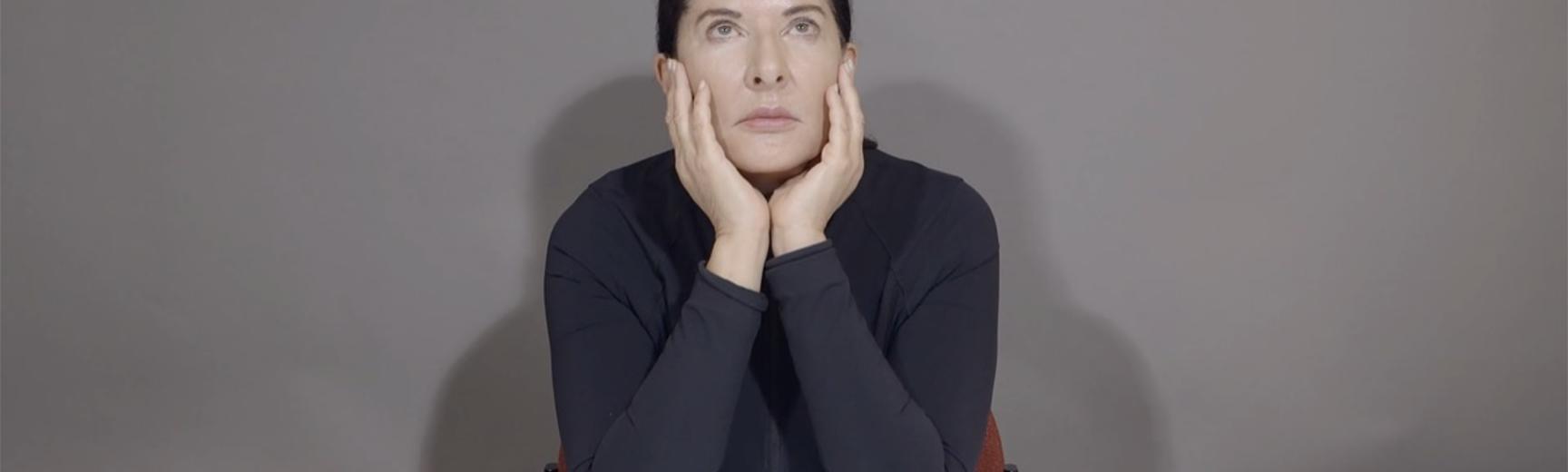

The results of the artist’s research can now be viewed in a large case display in the heart of the museum. Designed as a site-specific intervention in dialogue with the historic galleries of the Pitt Rivers, it presents one of the many objects that Abramović interacted with, the so-called ‘Witch’s Ladder’, alongside the artist’s responses to it: a set of drawings and a new video work entitled ‘The Witch Ladder’. That film, and a longer video called ‘Presence and Absence’, were recorded during a day-long shoot behind the scenes in the museum, when the artist engaged with thirteen artefacts she had specifically chosen to take off display. In line with the intense bodily practice she is renowned for, Abramović interacted performatively with each item. First, she choreographed her hands around it, to sense its aura. Then, once the object had been removed, she held its energy in the empty space left behind.

For Abramović: “Emptiness is so important. I believe that when you sit in one position for a long period of time and then go away, the energy is still there. Energy stays in the space.”

This concept was fundamental for the artist’s celebrated long-duration performance at MOMA New York in 2010, when she sat at a table in silence for eight hours a day for three months and museum visitors took turns to sit opposite her, locking eyes with the artist and often experiencing powerful emotions. It is also related to Abramović’s interest in the yogic and meditational practices of Tibetan Buddhism. In her conversations with Tibetan Buddhist teachers, Abramović had been introduced to the notion that emptiness can have a kind of fullness.

When encountering the famously full Pitt Rivers, Abramović said that she experienced it as an enormous force field, replete with the energies of objects and of their former owners and users. In reanimating those energies her work in the museum gives presence to absences. It also allows us to see the museum differently, through the eyes of one of the leading figures of the international contemporary art world.

‘Portals and Gates: Conversation with Marina Abramović’, by Clare Harris

Marina Abramović: “I want to talk with you about the ideas behind my exhibition in Oxford. There are just two pieces in the [Modern Art Oxford] show: a set of gates and a portal. Every single culture has a relationship to portals and gates but in many different ways. I am curious to know what you think when I say ‘portal’.”

Clare Harris: “At a general level, the portal may be a site of transition between life and death and between different states of consciousness. A point where mind and body dissolve maybe. But when you speak of these structures or concepts in relation to your exhibition, I immediately think of the role of portals and gates within Tibetan Buddhism. I particularly like the idea that the public are going to interact with these concepts within the gallery space and become part of the piece, like performance artists themselves. It will very much be an embodied experience for the visitor. To me, gates and portals have particularly strong associations with concepts and practices in Tibetan Buddhism, as well as in Hinduism and other religious contexts in Asia. They make me think of that amazingly complex diagram used within Tibetan Buddhism, the mandala. Gateways are significant elements in both the meditational diagram and the physical buildings that are created according to the design of the mandala, since they are portals marking transitional or liminal areas. As you know, the mandala is a kind of cosmological diagram, made up of a concentric series of squares and circles, the outer ring of which is composed of all the elements of the universe. The Buddhist meditator primarily engages with it as a mental exercise, in which they envisage themselves passing from this elemental ring at the edge of the circe and gradually moving through different zones (which may look like gardens or charnel grounds) to reach the representation of a deity (depicted figuratively or just via a syllable from a mantra) at the hub of the circle. The circle is subdivided into the four quarters of the universe, with gateways marking the cardinal points at East, West, North and South. As far as I understand it, from speaking with Tibetans and from what I’ve read about Tibetan Buddhism, the practitioner thinks of themselves trying to enter the mandala by passing through these gateways to the temple or palace in which the deity resides. The mandala is more than just a conceptual thing, however. It’s also present in the Tibetan Buddhist landscape in the form of temples and monasteries that feature a series of walls and gateways that a devotee must pass through to reach the central shrine. By entering a religious space like this, they seek to get closer to the most potent sacred object or person within that building. As such, the mandala is not just an image with doorways that may open into new forms of consciousness at a cognitive level, it can also be something highly material that Tibetans encounter on a quotidian basis, or that they go in search of on pilgrimages to remote sacred sites. The arduous nature of getting to such places and the wider effort involved in pilgrimage can be very powerful and transformative.”

Marina Abramović: “You open so many doors in my thinking. The portal, for me, is really about that changed state of consciousness. It’s about going to different time dimensions and from the cosmic to the earthly. But then I think the physical body can also be a gate. The difference between portal and gate may be something that arises from conditioning the body to get into the portal. For me the gate is something you go through, and the portal is how transformations happen. I watched Tibetans doing prostrations in Dharamsala (the Tibetan ‘capital in exile’ in India). In those places there were women who, even if they were not in good physical shape, would prostrate in front of the temple for up to twelve hours a day. It’s extraordinary. Normally nobody could do that because it just hurts, but they seemed to be oblivious to the pain. I think this is a kind of necessary physical conditioning and preparation which can get the body into the state that makes it possible to become a portal.”

Clare Harris: “Like you, I have seen Tibetans doing multiple full-length prostrations on many occasions; often they have been done by very devout members of the older generation. I have witnessed that in Tibetan refugee communities in India, as well as at sites in Lhasa (the original Tibetan capital), such as the Potala Palace or Jokhang Temple. There, people spent a significant amount of time prostrating at the entrance to the Jokhang, positioning their bodies in relation to the most sacred object in it: a statue of the Buddha. Tibetan Buddhist practices of this sort are like an offering of a kind of spiritual and bodily labour. In doing them, the practitioner may learn to move beyond pain. But ultimately what a Buddhist is trying to achieve is the accumulation of merit that will bring a better life in the next incarnation. In making those physical gestures in front of a sacred building, they’re making an offering of devotion to everything ranging from the most important person who has occupied it, such as the Dalai Lama, whose former home was the Potala Palace, to the Buddha himself, who is represented as a statue in the centre of the Jokhang, as well as to the principles of the religion in general. I imagine one of the things you’re most interested in is the degree to which consciousness may be changed by physical actions of that sort. But because I have never done more than a few prostrations, I don’t know how that happens! You (along with many Tibetans) will understand that much better than me, because you’ve done these long durational performances when the body is pushed to its limit. From what you’ve told me about your observations and understanding of Tibetan Buddhism, this is why you deeply respect what many Tibetans do on a daily basis.”

Marina Abramović: “Clare, one thing that is wonderful about you and why I love talking to you is because you say certain things that are like a trigger for me. You know what the idea is about and help make sense of what I do sometimes. Artists often do things by intuition, without realising exactly what is going on. Then later on, by seeing the effect of the work and by saying certain things we get clarification from others. You said something incredibly important when you talked about offering labour, because offering labour is part of the process, and is the way we’re changing consciousness. That’s the essence of my performance work. That offering of labour is so much based on the Tibetan tradition for me – the kind of work that’s not obviously useful. It’s not like the work of building muscles or doing the gardening or constructing a house. I’m talking about something which is outside the normal and may not have any obvious sense to it, but it is all about the process. It’s like something I did for three months during a retreat in a Tibetan community in India: making little Buddhas by repeatedly filling a mould with clay. You make thousands of little Buddha images by putting in eight hours of labour per day. You may make a thousand or a million. Then the next three months labour of this sort is done in running water and you don’t see any result and touch it but for the water there is nothing. The result is not important. It is the process that matters. It’s about the physical preparation, the layout and the merit that lets us get close to the portal and open it. In contemporary art nobody ever makes a connection with that kind of thing and that’s why Tibetan Buddhism is so important to me.”

This is an extract of a longer conversation between Marina Abramović and Clare Harris from a new book published to coincide with exhibitions at Modern Art Oxford and at the Pitt Rivers Museum: Marina Abramović, Gates and Portals, eds. Amy Budd, Dominik Czechowski and Clare Harris (Oxford: Modern Art Oxford in association with Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2022). You can read the full conversation online here (PDF) or below.

Acknowledgements and Credits

- Exhibition curated by Clare Harris with curatorial support by Nicholas Crowe

- Conservation by Andrew Hughes and Jeremy Uden

- Object photography by Henrietta Clare and Malcolm Osman

- Digitisation by Philip Grover

- Case design and installation by Alan Cooke and Josh Rose

- Photography by Tim Hand

- Print design by Creative Jay

- Digital support by Katherine Clough

The Pitt Rivers has been honoured to host Marina Abramović and her work at the museum. Our enormous thanks to Marina, to her Executive Director Giuliano Argenziano, and to all the team at her studio. We are very grateful to Modern Art Oxford for this successful partnership, with particular thanks to Paul Hobson, Amy Budd, Emma Ridgway, Clare Stimpson, Jess Robertson, Dominic Czechowski, and Hannah Healey. The Lisson Gallery generously loaned the ‘Witch Ladder’ drawings.

Marina Abramović @ Pitt Rivers Museum was curated by Prof Clare Harris in collaboration with many staff of the Pitt Rivers Museum. Special thanks to: Nicholas Crowe, Philip Grover, Thupten Kelsang, James Horrocks, Katherine Clough, Louise Hancock, Zena McGreevy, Alan Cooke, Josh Rose, Jeremy Uden, Andrew Hughes, Hannah Bruce, Catherine Booth, Karrine Sanders and the Director, Prof Laura Van Broekhoven.