Heritage Behind Glass

This page is the culmination of Chinaza Ruth Okonkwo's MSc Digital Scholarship practicum placement at the Pitt Rivers Museum focused on exploring Igbo cultural practices, including masks, uli, and masquerades. It has been created as a digital resource as part of the placement brief, reflecting on the poignant experience of seeing these vibrant cultural elements confined and displayed in colonial museums.

Who are the Igbo?

The Igbo people, also known as the Igbos, are an ethnic group indigenous1 to the southeastern region of Nigeria. The term "Igbo" encompasses the territory where the largest concentration of Igbos live, the domestic speakers of the Igbo language, and the language itself.

Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that humans inhabited Igboland long before the Bantu migrations, which spread from southeastern Nigeria across much of sub-Saharan Africa between 500 B.C. and 200 A.D2 . According to John N. Oriji, these studies indicate that the Igbo have a deep historical presence in their current homeland.

Igbo oral traditions often emphasize their autochthonous origins, asserting they are "nwa ala" (children of the soil). These traditions recount that Chukwu, the Supreme God, created the Igbo people directly from the land. One such story describes how Chukwu planted the Igbos into the soil, where they sprouted and came into being in Igboland.3 Another tale tells of Chukwu creating man and sending a smith to dry the land, bringing forth yam and cocoyam, and establishing market days.4 These narratives, though seemingly mythological, reflect a strong belief among the Igbo that they are indigenous to their land and did not migrate from elsewhere.

The Igbo political system is characterized by kinship egalitarianism, where equal relations are expected among kin. This system fostered peace and social stability, allowing for individual distinctions through title-taking and wealth without disrupting the overall egalitarian structure. This balance of equality and individual recognition has been a key element in Igbo society, contributing to its cohesiveness and resilience.

Wooden female figure in black with white, red and yellow painted decoration. Onitsha, Anambra State, Nigeria.

Carved and painted wooden figure of a woman seated on a stool and nursing a child. Enugu State, Nigeria.

1 The use of the term indigenous is deliberate and political. It aims to redefine the notion of indigeneity to include certain ethnic groups within the African continent. I strive to incorporate this redefinition to counter the harmful narratives of colonialism, specifically the way African history and culture are reduced and diminished solely to encounters with European colonialism. The history of the Igbos is vast and long-standing, existing a millennia before their first encounter with the British.

2 Oriji, John Nwachimereze. 1994. Traditions of Igbo Origin: A Study of Pre-Colonial Population Movements in Africa Rev. ed. New York: P. Lang.

3 Afigbo, A. E. 1983. “Traditions of Igbo Origins: A Comment.” History in Africa 10: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/3171687

4 Afigbo, A. E. 1983. “Traditions of Igbo Origins: A Comment.” History in Africa 10: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/3171687

Masquerades

In Igbo society, the institution of masquerades, known as mmanwu, holds a position of both fear and respect. Masquerades are perceived as spiritual beings manifest physically through their masked forms, embodying supernatural powers and otherworldliness. Mmanwu serves critical judicial and executive roles, leveraging their perceived spiritual connection to deities to determine truth and justice. They adjudicate disputes between individuals, such as between marital conflicts and groups. It is widely believed that lying to a masquerade results in severe consequences, such as death or misfortune, making their judgments final and indisputable.

Mmanwu symbolize their mystical powers and distinction from living humans. They are classified similarly to human categories, with elderly male masquerades often serving as post-chanters, alongside adult male, teenage male, old female, and young female masquerades5. The old male masquerades, regarded as ancestors, are believed to return to their families, share symbolic meals, inquire about family affairs, warn of dangers, and rebuke those who disobey their instructions.6

Despite their spiritual importance, women are generally excluded from participating in the secret aspects of masking or controlling a masked spirit. This exclusion prevents women from playing a significant role in shaping and evaluating taboos and crimes within the masquerade system. However, in some Igbo communities (obodos), women past menopause who have ritually transformed7 into men are allowed to own masks and participate in masquerade societies. However, this practice is rare and usually restricted to certain villages. In most of Igboland, a woman becoming a masquerade is considered an abomination.

Igbo masks are typically deployed in response to significant and complex issues, unlike the regular and direct use of masks by the Igala and Cross River peoples. In Igbo culture, masks perform major sociopolitical functions during times of stress when other methods have failed.

As an art practice and performance tradition, Igbo masquerade theater maintains a uniform practice with diverse expressions across different regions8, reflecting its rich oral tradition and cultural significance.

5 Egudu, R.N. 1992. African Poetry of the Living Dead: Igbo Masquerade Poetry. Edwin Mellen Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=-wKDAAAAIAAJ

6 Egudu, R.N. 1992. African Poetry of the Living Dead: Igbo Masquerade Poetry. Edwin Mellen Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=-wKDAAAAIAAJ

7 In most instances, gender was closely linked to biological sex, yet it also functioned as a sociopolitical tool that could be altered through specific rituals. Certain women and men had the ability to change their gender status. Women could socially transition into the role of men, allowing them to participate in male-dominated spaces and roles, and be acknowledged by others as male. This transition was typically undertaken by women who had significant wealth, social influence, and, crucially, the consent of the entire village. The flexibility in Igbo gender roles does not necessarily indicate a progressive stance on gender ideology. Eldest daughters could become sons in the absence of male heirs to continue their father's lineage. Similarly, women could take on the role of husbands to secure their legacy and wealth through descendants, or if they were unable to bear children. Additionally, a post- menopausal woman was no longer regarded as a "woman" due to her inability to reproduce. As a result, she could participate in male activities, such as masquerades, after undergoing a ritual and formal transformation into a man.

8 Ukaegbu, V. (2007) The Use of Masks in Igbo Theatre in Nigeria: The Aesthetic Flexibility of Performance Traditions. Lewiston, N.Y.; Lampeter: Edwin Mellen Press. 9780773451759

Uli

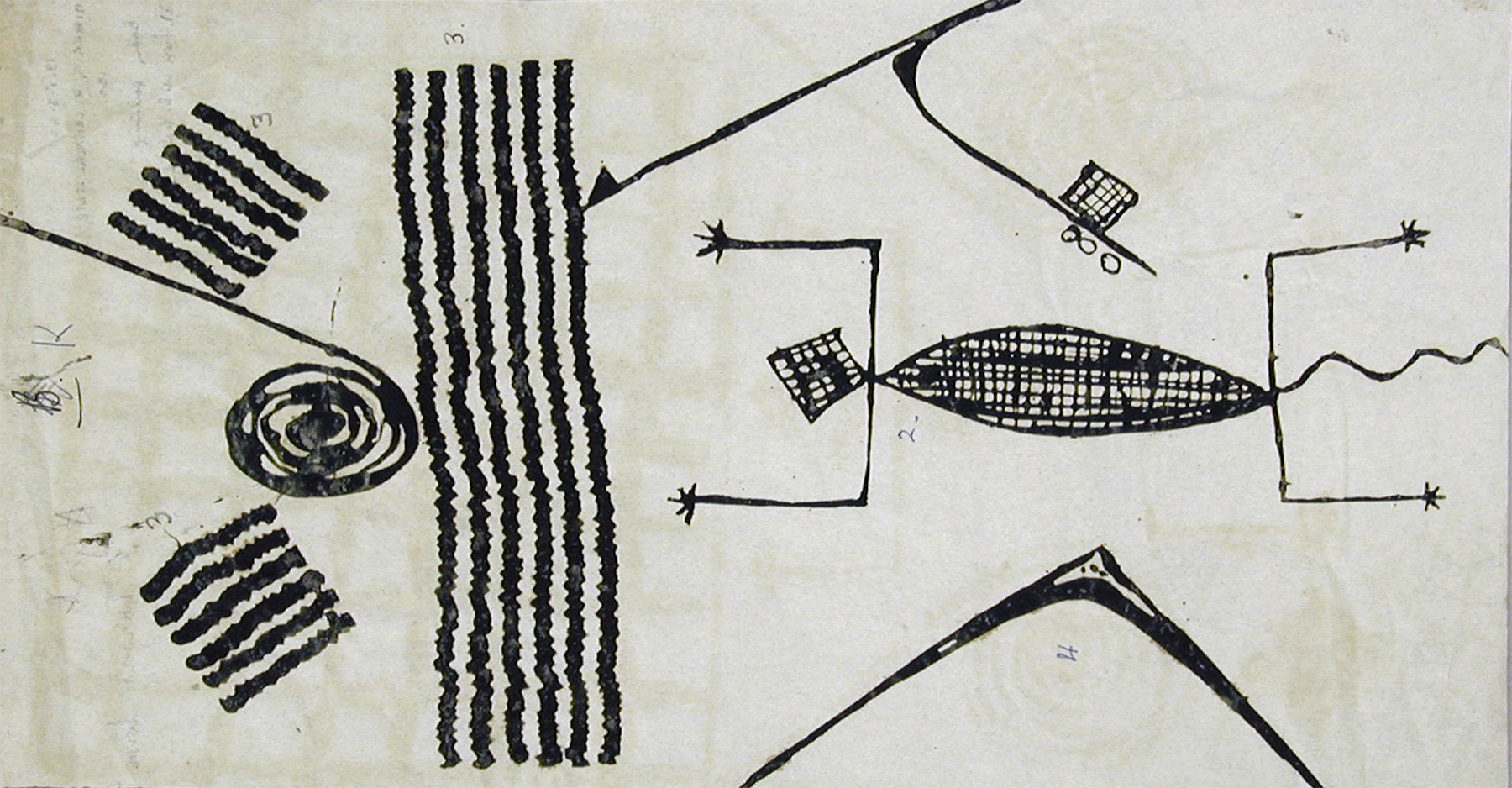

Before colonization, uli painting was a treasured artistic tradition in Igbo culture, regarded as a divine gift from Ala, the earth goddess, to Igbo women. Uli represents beauty and virtue, passed down through generations of women, typically learned during their coming-of-age ceremonies.9

Traditionally, Igbo women adorned their bodies and others in their community, including males and children, and clay walls with uli designs. Still, uli designs also appeared on masks, hairstyles, engraved household items, and pottery. Uli was prevalent throughout Igboland, serving as a vibrant artistic expression and a medium to convey socio-cultural values and meanings10. While everyday designs were simple, intricate patterns were reserved for important occasions like weddings, title ceremonies, and funerals. Despite their detailed application, uli body designs faded after about a week, and murals washed away during the rainy season. This ephemeral quality is a hallmark of uli. Early missionaries and colonial figures attempted to preserve uli through photographs and drawings, but the Igbo people embraced its transitory nature, believing in a "third eye" that enabled them to recall and reconstruct the art’s memory and meaning.11

9 Thompson, B., & Amadiume, I. (2008). Black Womanhood: Images, Icons, and Ideologies of the African Body (1st ed.). Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College in association with University of Washington Press.

10 The Nsukka Group. “The Uli Aesthetic.” The Poetics of Line, The Sylvia H. Williams Gallery, africa.si.edu/exhibits/uli.htm

11 “Uli Designs: Ìgbò People, Nigeria, 1930s–1940s.” Body Arts, The Pitt Rivers Museum,

web.prm.ox.ac.uk/bodyarts/index.php/temporary-body-arts/body-painting/196-uli-designs.html

12 Browne, Grace. (2020) “Uli Art, The Pursuit of Beauty.” Alache, alache.wordpress.com/2020/09/04/uli-art-the-pursuit-of-beauty/

Listen to a reflection and critique

Museum label written directly onto the back top corner of a carved and painted wooden sculpture of two human figures on four-legged pedestal, representing a spirit. Aboh, Delta State, Nigeria.

Interior view of a face mask from Okorosia masquerade. Eziama and Orlo village groups, Imo State, Southern Nigeria.

Interior view of a face mask from Okorosia masquerade. Southern Nigeria.

Transcript of reflection audio:

As an Igbo person in the 21st century, witnessing the material aspects of Igbo culture colonized, categorized, and sequestered in institutions like the Pitt Rivers Museum evokes profound pain and confusion. The experience underscores the dehumanization of Igbo culture, where sacred objects such as masks and masquerades, once imbued with spiritual power and deep cultural significance, are now rendered powerless behind glass displays. The masks, labeled with meaningless English identifiers, become artifacts stripped of their essence and context. It reinforces that we have been defeated, and our beliefs have been made foolish and impotent.

Why run in fear of the masquerade and confess one’s sin when it has been captured by unbelievers and foreigners, sprayed and manipulated with pesticides, and hung up to be either stared at or ignored? One can't help but wonder if the spirits of our ancestors haunt these sterile halls, yearning for the vitality and reverence they once commanded.

The treatment of uli art forms, captured and confined, starkly opposes their original intent. With its transient beauty and ephemeral nature, uli was never meant to be locked away or preserved in static forms. Its capture and display reflect a profound misunderstanding and disrespect for its cultural significance. The colonization of Igboland and the subsequent erasure of uli from our landscapes disrupted the generational transmission of this art, silencing the vibrant dialogues between women and their communities.

The purpose and relevance of institutions like the Pitt Rivers Museum must be questioned. While museums often claim educational purposes, one must ask how many visitors genuinely engage with the cultures represented, including the Igbo. How many go beyond surface-level curiosity to conduct deeper academic research, seeking to understand the context and significance of the objects they see? The tension within European museums is palpable, and mere calls for decolonization are insufficient to address the underlying issues.

The museum's claim to care for and preserve these cultural elements rings hollow when it continues to keep and label them away from their people. Some cultural expressions, like uli, were never meant to be preserved in stasis; they were intended to be continually made and remade, a living testament to the creativity of the Igbo people as well as their belief gained from millennia of autonomy that they would continue to be free, changing and developing in their own right. Like so many other indigenous groups, they did not expect to be colonized and, therefore, did not create and live with the idea that all aspects of their life needed to be preserved in the manner Western society demanded. The ongoing colonization of these spaces by museums limits the capacity for cultural renewal and remaking, perpetuating a cycle of cultural stagnation and loss.

In essence, the preservation of Igbo material culture in museums under the guise of education and preservation often results in the very opposite: the silencing and stifling of dynamic cultural practices that were meant to evolve and thrive within their communities. A third museum is not possible13. Calls for decolonization are not enough if they are not calls for abolition. True preservation occurs when culture can flourish, develop, and change autonomously.

13 Yang, K. W. (2017). A third university is possible. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

References

Afigbo, A. E. 1983. “Traditions of Igbo Origins: A Comment.” History in Africa 10: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/3171687

Browne, Grace. (2020) “Uli Art, The Pursuit of Beauty.” Alache, alache.wordpress.com/2020/09/04/uli-art-the-pursuit-of-beauty/.

Egudu, R.N. 1992. African Poetry of the Living Dead: Igbo Masquerade Poetry. Edwin Mellen Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=-wKDAAAAIAAJ

Oriji, John Nwachimereze. 1994. Traditions of Igbo Origin: A Study of Pre-Colonial Population Movements in Africa Rev. ed. New York: P. Lang.

The Nsukka Group. “The Uli Aesthetic.” The Poetics of Line, The Sylvia H. Williams Gallery, africa.si.edu/exhibits/uli.htm

Thompson, B., & Amadiume, I. (2008). Black Womanhood: Images, Icons, and Ideologies of the African Body (1st ed.). Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College in association with University of Washington Press.

Ukaegbu, V. (2007) The Use of Masks in Igbo Theatre in Nigeria: The Aesthetic Flexibility of Performance Traditions. Lewiston, N.Y.; Lampeter: Edwin Mellen Press. 9780773451759

“Uli Designs: Ìgbò People, Nigeria, 1930s–1940s.” Body Arts, The Pitt Rivers Museum, web.prm.ox.ac.uk/bodyarts/index.php/temporary-body-arts/body-painting/196-uli-designs.html

Willis, L. (1989). “Uli” Painting and the Igbo World View. African Arts, 23(1), 62–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/3336801

Yang, K. W. (2017). A third university is possible. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Extended Bibliography

An extensive bibliography is available to download here covering various aspects of Igbo history and culture. Some of these articles and monographs are unrelated to the topics discussed, but I encourage all readers to explore and learn about Igbo culture.

Image credits for banner images (from top to bottom):

Top banner: Painting of uli body painting designs on paper, East Central State, Nigeria. PRM 1975.3.36.

Masquerades banner (left to right):

Face mask from Okorosia masquerade. Eziama and Orlo village groups, Imo State, Southern Nigeria. PRM 1935.73.2.

Face mask from Okorosia masquerade. Southern Nigeria. PRM 1938.15.11.

Face mask from Okorosia masquerade. Southern Nigeria. PRM 1938.15.12.

Uli banner: Uli body painting designs on paper, Arochukwu (uncertain), Nigeria. PRM1972.24.149.

Uli banner: Painting of uli body painting designs on paper, Anambra State, Southern Nigeria. PRM1975.3.36.