The Time of the Brave

The Time of the Brave

Introducing the Niger Delta's Agaba masquerade

Long Gallery, 28 Jan 2023 – 7 Jan 2024

The Mask arrived appropriately on the crest of the excitement. The crowd scattered in real or half-real terror. It approached a few steps at a time, each one accompanied by the sound of bells and rattles on its waist and ankles. Its body was covered in bright new cloths mostly red and yellow. The face held power and terror; each exposed tooth was the size of a big man’s thumb, the eyes were large sockets as big as a fist, two gnarled horns pointed upwards and inwards above its head nearly touching at the top. It carried a shield of skin in the left hand and a huge matchet in the right.

‘Ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-oh!’ it sang like cracked metal and its attendant replied with a deep monotone like a groan:

‘Hum-hum-hum.’

‘Ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-oh.’

Oh-oyoyoyo-oyoyo-oyoyo-oh: oh-oyoyo-oh. Hum-hum.’

There was not much of a song in it. But then an Agaba was not a Mask of song and dance. It stood for the power and aggressiveness of youth.(Chinua Achebe Arrow of God, 1964)

The above words are from Chinua Achebe’s novel, Arrow of God, in which he describes the drama of the Agaba mask’s awesome and terrifying performance. Films shot by missionary G.T. Basden n the 1930s capture the spectacle. The mask is sometimes known as Mgbedike: time of the brave. Before colonialism and its economies of extraction, the mask was part of the fabric of a rural world where the supernatural reinforced the structures of village authority, and in colonial propaganda films, like the Oscar-winning Daybreak in Udi (1949), Agaba masqueraders represented the forces of tradition.

Mgbedike dance, film still from recording by George T. Basden, 1930. Copyright Bristol archives 2006/070/1/2.

But masking is not stuck in this rural past and Agaba is also a modern urban mask. The city of Port Harcourt was the catalyst for Nigeria’s incorporation into the global economy of energy capitalism: first with coal and later oil. The city grew around this masking tradition and Igbo traders celebrated Agaba at festivals. Reflecting popular Hollywood movies of the time their groups were named Montana in reference to Buffalo Bill films.

Later, after the Nigerian Civil War (1967-70) when the Igbo traders left the city, the masquerade was taken over by others who named their mask 007 after the James Bond movies. As it traced the violent historical contours of the Nigerian oil state, the mask slipped from an ethnic designation to a generational one and became a play of and for the youth of the Niger Delta. Performing the masquerade has always been a test, a way of proving manhood and masculinity. Just as Achebe had declared, Agaba stands for the power and aggressiveness of youth.

Agaba is a spirit in the city whose history captures the spirit of the city. Port Harcourt has borne the violent legacy of oil since its discovery in the late 1950s and the arrival of the multi-national companies headquartered there. The city’s history, and that of the oil-producing Niger Delta, is often presented as an intergenerational crisis. Youth are painted either as victims who are excluded from the profits of the oil economy by powerful patrons, or vanguards of sometimes violent claims for oil revenue based on indigenous rights.

E.H. Duckworth. An Igbo dancer at Okitipupa, Ondo Province. 1949. (1998.194.22). This image records Igbo traders performing their Agaba masquerade across different regions of Nigeria in the 1940s.

The Agaba masquerade offers the potential for protection and profit in this patrimonial political economy. It often performs to celebrate ‘big men’ in the city. Before becoming a traditional ruler, Agaba’s ‘grand patron’ ’Chief Ateke Tom was leader of the Niger Delta Vigilante, an armed militia group that came to the fore in a violent insurgency in the early 2000s. This political order is never far from the surface of the Agaba song repertoire, and folk heroes including the murdered rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and journalist Dele Giwa feature in praise songs and laments.

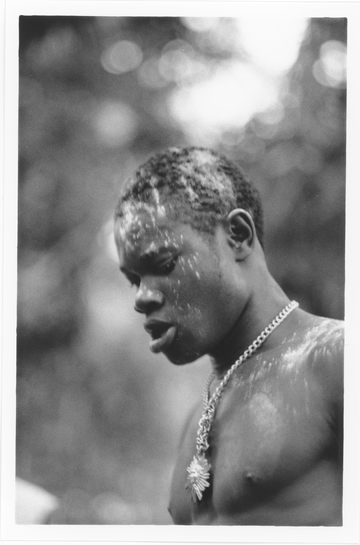

Today Agaba is performed across the Niger Delta where it adapts to different local aesthetics. The group performing here in Port Harcourt is called Area United. The carnivalesque atmosphere is a hyper-masculine space of conviviality and camaraderie. Members whip each other without flinching to demonstrate their courage. The mask must be protected by eggs which are smashed into its face. The red flag signals danger; the black flag indicates remembrance. Carrying the heavy mask demands skill and strength. Masking is an ordeal, a test of power and authority. Those who succeed are ‘rugged’ ‘men.

Portraits of Warrior, Akwa Ibom State, 2003

Richard Udoka was popularly known as Warrior. Growing up in Port Harcourt, Warri and Bonny, his life mirrored that of many youth of the Niger Delta. He joined student cults (gangs) at school in Benin City, and recalled violent confrontations with ‘debam’, a street gang, while living in Diobu, Port Harcourt. At home in Akwa Ibom State Warrior was involved in the smuggling of crude oil (bunkery), and became a local youth leader. He was courted by politicians to provide protection for their campaigns. And in 2017, during worsening cult violence, his political patron, who had just been sworn in as secretary to the local council, and whose was nickname was ‘Strong’, was assassinated. Warrior was killed in the same attack by the Icelander gang. Warrior loved playing the Agaba masquerade. He explained that people did not understand that Agaba was a positive force in young men’s lives; ‘They see black on black’, he said, 'and think rough boys. But they do not know that it is for good – it is to help protect us’.