Conservation case study: Lakota war bonnet

This war bonnet was made by the Oglala Lakota, one of the tribes comprising the 'Great Sioux Nation'. Displayed in the Museum's Lower Gallery, the headdress illustrates how traded goods were appropriated and included into Native American material cutlure.

The war bonnet is thought to have been collected by William Blackmore, an English businessman who showed avid interest in the life and customs of Native American people in the mid-19th century. He was an investor and philanthropist in North America, and his position would have allowed him contact with the leaders of different indigenous tribes.

Blackmore likely obtained the war bonnet during an expedition to the American West in 1872, possibly from Oglala Lakota war leader Red Cloud. In 1931, the headdress was acquired for the Cranmore Ethnographical Museum by Harry Beasley, and was subsequently donated to the Pitt Rivers Museum in 1954 by his widow.

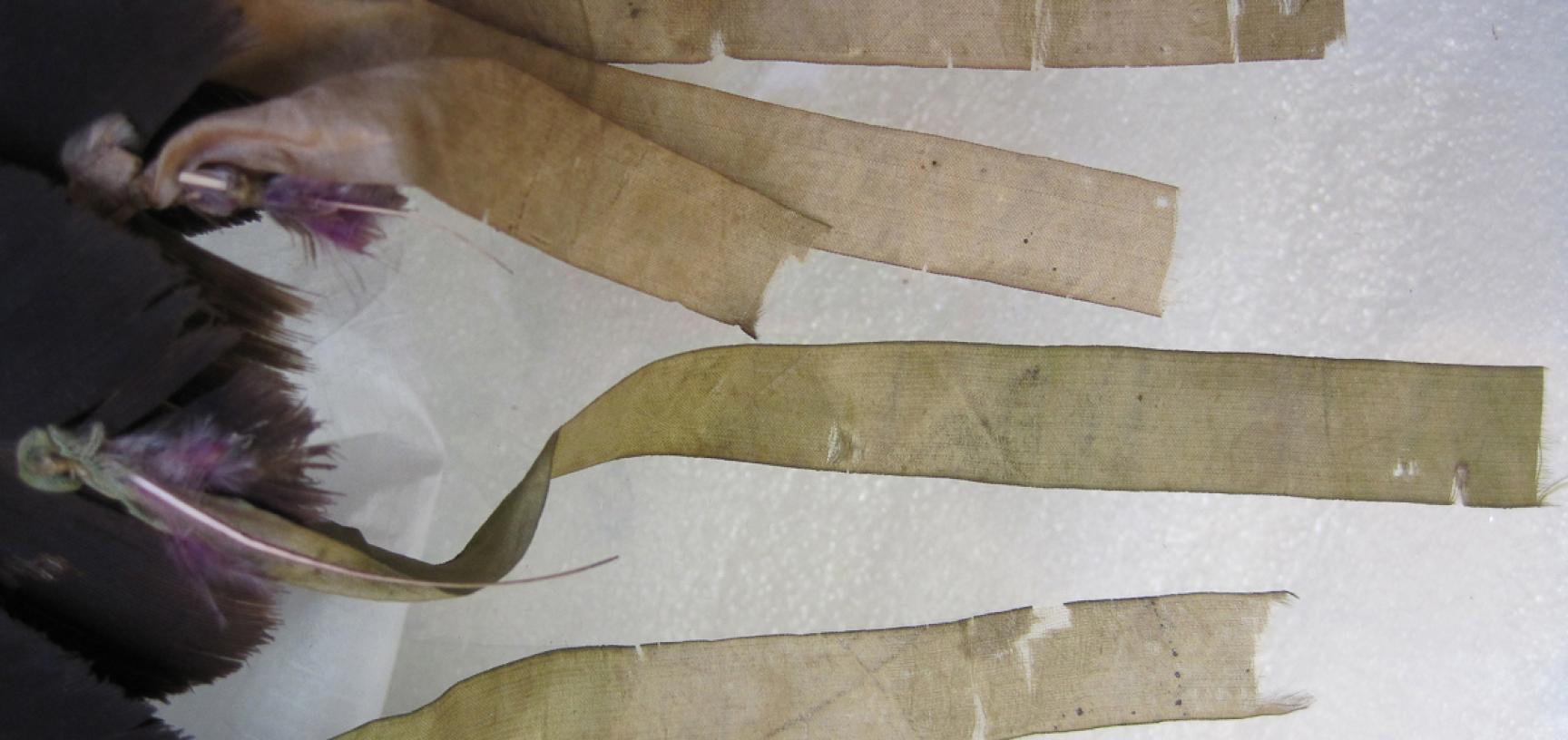

The central part of the war bonnet is composed of a simple cap attached to a long trail. This structure is made of semi-tanned animal hide, most likely American bison, a mainstay resource for the people of the Plains. The length of the trail seems to indicate that the headdress was probably designed to be worn when riding a horse. The headdress is adorned with 76 feathers from an immature golden eagle. On the Plains, war bonnets decorated with golden eagle feathers were highly signficant items, symbolising the honour and esteem of the wearer.

The feathers are attached through performations in the hide, using the 'quill-loop' technique around a thin strip of leather. Another similar strip runs through the shafts, keeping the feathers aligned.

Alongside these indigenous materials, several traded goods have also been incorporated into the headdress. The patterend textile covering the trail is printed American cotton, while the coloured beads decorating the headband are European in origin. The bright red cloth, finishing the trail at one end and adjoining the cap at the other, is Stroud cloth from England. The once colourful (but now faded) silk ribbons knotted to the tip of the cap feathers are also a traded commodity.

For many years the war bonnet was kept flat and folded in storage, accessible only to researchers. Over time, many of the materials began to deteriorate and weaken due to damage caused by insect attack and the accumulation of Museum dust. Poor storage had also caused deformations and breakages in many of the feathers. Consequently, an assessment of the war bonnet's condition in 2011 identified cleaning and stabilisation as treatment priorities to prepare it for display.

It is a challenge for a conservator to treat a composite object such as this. The presence of such a diverse range of materials calls for the careful consideration of treatment options, balancing the differing needs of each material against the rest and finding appropriate solutions that accommodate the object as a whole.

Both dry and wet cleaning methods were applied to the feathers. Brushes, a vacuum and special rubber sponges were first used to remove as much dust as possible before employing solvents for a final clean. Repeairs were then made to several damaged shafts using new colour-matched quills, polyester threads, and adhesives.

The crumpled and fragile silk ribbons were humidified and then smoothed out with the application of small weights. Many of the ribbons were then supported with dyed-to-match silk crepeline fabric impregnated with adhesive. Elements of the patterend cotton were also reshaped using smilar humidificaton techniques.

A large missing area in the woollen Stroud cloth was filled and supported with red silk crepeline that was then needle felted with wool to match both the colour and texture.

The war bonnet is an excellent example of how sympathetic conservation can give a new lease of life to an object. Clean and stable, it is now in a condition where its form and function can both be safely presented to the public.

The conservation of the war bonnet took nearly 150 hours of practical treatment and research.